Shannon May and Jay Kimmelman decided to set up a for-profit operation to run

schools in Africa.

Their business model appeared to be:

- Underpay teachers by about 60%.

- Inflexible curriculum.

- Poor vetting of teachers and lax management.

- Break local laws. (They call it,"Disruption.")

-

Vociferous pursuit of critics, including what appears to be an attempt to

inspire mob violence against them/

If this sounds a lot like charter schools in the United States, you would be

right.

It appears to be

collapsing into a morass of corruption and greed:

In the early days of the era of Silicon Valley disruption, two Harvard

University graduates dreamed up a bold experiment in education.

Shannon May, who studied education development in rural China,

and her husband, Jay Kimmelman, an education software developer, spied an

untapped opportunity for some of the moving-fast-and-breaking-things going

on all around them.

They call it disruption. People with functioning senses of right and

wrong call crimes.

………

Over the next decade, Bridge grew into a chain of

schools providing a homogeneous curriculum developed by researchers in

Cambridge, Massachusetts, to hundreds of thousands of students in Kenya,

Uganda, Nigeria, Liberia, and India. Today, it is the largest for-profit

primary education chain in the world.

As the company

mushroomed, it found ready investors. “It was not social impact

investors,” May said in a 2016

MIT video case study, “it

was straight commercial capital who saw, like, wow, there are a couple

billion people who don’t have anyone selling them what they want.”

But the social impact investment crew was behind Bridge, as

well. The company is financed today by some of the highest-profile do-good

donors in the game — or rather, the for-profit arms of their networks,

including Chan Zuckerberg Education, LLC, linked to Mark Zuckerberg;

Pearson Education; Gates Frontier LLC, tied to Bill Gates; Imaginable

Futures, linked to eBay billionaire Pierre Omidyar, a major funder of The

Intercept; and Pershing Square Foundation, tied to billionaire hedge fund

mogul Bill Ackman. The United Kingdom’s development bank, the European

Investment Bank, and the International Finance Corporation of the World

Bank funded it too.

To become profitable, May and Kimmelman had

to scale up quickly while keeping costs down. “Bridge International

Academies was founded from day one on the premise of this massive market

opportunity, knowing that to achieve success, we would need to achieve a

scale never before seen in education, and at a speed that makes most

people dizzy,” an

early version

of the company’s website boasted. To do well with small margins, thousands

of classrooms would be needed, because each classroom could bring in a

profit of just tens of dollars a month. “The urgency is because the only

way you can have a price of $5 a month is if you have hundreds of

thousands of customers. We need 500,000 pupils to break even,” May

said in 2013.

Their idea of how to accomplish such scale was

straightforward: The largest cost when it comes to education is teacher

salaries. But if curricula can be centrally produced and distributed on

tablets that teachers read to the class, word for word, then teacher pay

can plummet.

What they are saying here is that Africans are stupid, and they are worthless

as teachers, so they can hire parrots instead of teachers.

That, May believed, would not hurt the quality of education children

received. While the school reform movement in the United States at the

time was fighting against what it called “the soft bigotry of low

expectations” — easier curricula for minority students that reflected

racist assumptions about their learning capacity — May argued that in

Africa, high expectations are bigoted. “‘Don’t you have to have brilliant

teachers in every room in order to have a well-educated child?’ ’Cause

honestly, that’s how a wealthy person would think of it,” May

explained. “You can’t

have a brilliant-teacher hypothesis and expect to change the education for

hundreds of millions of children.”

So, you are saying that second best is OK, because Africans are not real people who deserve the full rights and consideration as human beings.

Your business model is basically the Dredd Scott v. Sandford.

It was also appropriate to pay those teachers less, she argued.

“You have to be able to upscale the teachers that would be available

within the same community as your child. How are you going to get tens of

thousands, eventually hundreds of thousands, of teachers to be working

with hundreds of millions of impoverished children? They need to be from

the same community. They need to face similar challenges. But also

economically, they need to be part of the same economy.” Hiring teachers

who are “part of the same economy” meant paying them just a few dollars a

day.

………

In 2022, Nobel Prize-winning

economist Michael Kremer conducted

a study

in Kenya to assess the efficacy of standardized learning at Bridge

schools. The resulting report, which Bridge heavily promotes, found that

public school teachers in Kenya were paid between $235 to $392 per month

plus generous benefits, while Bridge teachers worked longer hours but

earned around $80 per month with considerably fewer benefits than their

public school counterparts.

“By not requiring post-secondary

credentials, which typically represent a smaller share of the labor force

in lower-middle income countries, Bridge has been able to draw from a

larger pool of secondary school graduates,” the study read.

So, a high school diploma enough, and no training because it's all in the software. I'd never trust that to my car mechanic, much less someone teaching my children.

………

Bridge also whacked away at the second highest education

costs: facilities. According to Kremer’s study, while public schools in

Kenya were required to have stone, brick, or concrete walls, Bridge

designed standardized schoolhouses largely out of wooden framing and mesh

wire, enclosed by iron sheeting —

derisively dubbed “chicken coops for kids.” “Bridge’s founders recognize that the model

deprioritizes physical infrastructure and they have argued that this frees

up resources for expenditure on other inputs that can improve school

quality,” the Kremer study noted. “Bridge schools are not made of ‘mesh

wire’; they have windows with mesh wire,” a Bridge spokesperson said.

So, poorly trained teachers, poor facilities, disdain for the students and staff, and a desire for rapacious profit.

If that ain't a recipe for bad education, I don't know what is.

“Our biggest challenge is that we need to ensure we

standardize everything,” Kimmelman was quoted as saying in “Bridge

International Academies: School in a Box,” a

2010 Harvard Business School case study. “If we want to be able to operate like McDonald’s we need to make sure

that we systematize every process, every tool, everything we do.” They

later revised it for branding purposes to “academy in a box,” May said,

“when we realized everyone here calls a private school that’s good an

academy.”

McDonald's? Seriously? And people thought it was making the world a better place?

I am sure that it made the world a better place for May and Kimmelman, who doubtless were well paid by venture capitalist cash.

Investors were familiar with the model: The company

would understandably lose money in the early years, but as long as growth

was steady, profitability could ultimately be reached. And, with enough

scale, it might eventually loosen regulatory obstacles in the same way

that ride-hailing app companies

become too big

for a city or state to do anything but accept them and adapt.

So, conspiracy to commit crimes, and once you are big enough, you are hoping to roll regulators and politicians, because criminality is at the heart of disruptor philosophy.

………

“Technically, we’re breaking the

law,” May said in a

2013 article

in the education publication Tes — a quote that was reused in a mostly

favorable 2017

New York Times profile of Bridge. “There would be more people and more organizations willing to

try and push the envelope and get higher pupil outcomes if the regulatory

and legal framework was less restrictive,” May went on. “You have to be

extreme. You have to take real risks to work in those environments. Often

there are [laws] preventing most companies from trying to figure out how

to solve these problems.”

Bridge quickly became the

darlings of the Davos world. World Bank President Jim Yong Kim

lauded the firm publicly in a 2015 speech. Whitney Tilson, a New York-based Bridge investor and hedge-fund

manager, called it “the Tesla of education companies”

in 2017.

What a surprise, an abusive and exploitative business model that gets rave reviews from the denizens of Davos.

Also, I can't believe that I am saying this, but that is unfair to Tesla.

Cory Doctorow calls this ensh$#tification, and normally a business has to be around for a while, but they baked this in from the start.

That year, Times columnist Nicholas Kristof lavished

nearly 1,000 words

of praise on Bridge schools in the West African nation of Liberia,

chastising teachers unions and other opponents of outsourcing public

education abroad to for-profit companies. “So, a plea to my fellow

progressives,” he concluded. “Let’s worry less about ideology and more

about how to help kids learn.”

Nicholas Kristof, the former New York Times writer who has an almost perfect record of not understanding charity and inequality.

If that ain't a red flag, I don't know what is.

………

Then, in March 2022, the World

Bank’s financing arm — the International Finance Corporation — quietly

divested from NewGlobe, the parent company of Bridge International. No

announcement was made. No reason was given. Just a

short disclosure

in small print at the bottom of a portal that reads, “Update: IFC has

exited its investment in NewGlobe Schools, Inc.”

So, they discovered something. Something bad.

Not a surprise when you hire the worst people and put them in the worst facilities, and assume that you can do this with litter or no oversight.

Among

locals and within the global network of civil society organizations that

work on development projects, rumors swirled that the dark side of

Bridge’s success may have played a role — specifically, a series of abuse

and neglect allegations in Kenya that had caught the eye of a

Nairobi-based human rights group, the East African Centre for Human

Rights, or EACHRights, as well as the internal watchdog at the World Bank,

known as the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, or CAO.

………

During

lunch break on a school day in the spring of 2016, David Nanzai, an

eighth-grade teacher at Bridge Kwa Reuben, a school in the Mukuru informal

settlements in Nairobi, found an anonymous handwritten note between the

pages of a Kiswahili textbook sitting on his desk.

………

Eventually, they

figured out who had written the note, and as they investigated further,

they found at least 11 girls, aged 10 to 14, had been assaulted. They

suspected three other girls may have been too frightened to come forward.

Reporting by The Intercept — including interviews with

parents, former Bridge teachers and staff, nonprofit workers, community

leaders, education activists, and police officers — corroborated the scope

and many of the details of the sexual abuse. Many of the sources asked for

confidentiality, expressing fear of reprisal from Bridge and concern about

a culture of secrecy.

Of course they had a culture of secrecy. That's Theranos, that's Silicon Valley in a nutshell.

Break laws and savagely enforce omerta.

………

Nanzai reported his findings to Josephine Ouko, his

school’s academy manager, similar to a principal. Ouko, whom The Intercept

was unable to reach for comment, called a staff meeting in her office with

the alleged perpetrator in attendance. The other teachers confronted him,

seething. Initially, he denied the allegations, according to four Bridge

teachers present, but the teachers played audio recordings of Nanzai’s

conversations with the students and shared their written testimonies.

………

After the meeting, the teachers expected Ouko, the

academy manager, to notify Bridge and call the police. But Ouko told them

to leave her office so she could speak to the teacher alone, the four

teachers said. The next thing they knew, the man had disappeared into the

maze of crowded dirt streets that make up the Mukuru informal settlements.

He was gone.

………

Told that The Intercept had identified the alleged perpetrator

by name, a Bridge spokesperson acknowledged the abuse had taken place and

confirmed the former teacher’s identity. Asked why the company had

previously dismissed our inquiry, the spokesperson said that the company

thought we were referring to different allegations.

Different allegations? Someone has been very remiss in their oversight.

And, in a

letter from Bridge’s attorneys, the company added the threat of a lawsuit

against The Intercept, citing the “potential for legal action” if the

story was published. “The rare and isolated misconduct of a few bad apples

should not tarnish the incredible work that these educators are doing in

their communities every day,” read a letter from Andrew Philips, an

attorney with Clare Locke LLP, positing that the problem was simply

endemic in Kenya. It was, he wrote, “important to acknowledge the sad

reality that sexual abuse of students by teachers has historically been a

serious problem in Kenyan schools.”

First, the saying is that "A few bad apples spoil the barrel."

Secondly, suggesting that you do not have to do proper oversight, because Kenya is, to quote Donald Trump, "A sh$#-hole country," is racist and dismissive.

The legal threat was a

glimpse into the aggressive posture Bridge had become known for, a

reputation that was forged in the global press amid its battle in Uganda

with a Canadian graduate student named Curtis Riep.

………

On May 30, 2016, just weeks after the

teachers and parents had reported the abusive teacher to the police in

Nairobi, Curtis Riep sat down in a café in Kampala, Uganda. A Ph.D.

candidate in educational policy studies at the University of Alberta, Riep

was in the city compiling a report on Bridge schools for Education

International, a global federation of teachers unions.

He had

managed to schedule an interview with a Bridge national director and a

regional manager. As the men began their conversation, Riep began

recording, as he did for all such meetings, so that he could later

transcribe the answers.

So Riep’s recorder was rolling when

moments later, a plain-clothed police detective dressed in a suit — or, at

least, a man identifying as one — and two self-proclaimed officers in

militarized uniforms carrying assault-style weapons approached the table.

Riep later transcribed the resulting exchange verbatim in his

dissertation.

“I work with the police — the Uganda police,”

the “detective” said to Riep after exchanging pleasantries with the

executives. “I’m going to be taking you now.”

………

It would later

emerge that Bridge officials in Uganda had accused Riep of gaining access

to Bridge schools by impersonating a teacher.

“There’s a

school where you went to,” the plain-clothed man claiming to be a police

detective said, telling Riep he “must come with me now.”

………

None of the three men with guns would identify

themselves, and Riep made one last bid to connect on a human

level with the Bridge director. “Please, I don’t know if

these are real police. I mean, I don’t want my life to be in

jeopardy. So, if you feel like you really need to protect

yourself and Bridge to this extent, I think it is a mistake.

Let’s not make this more of an issue. You are the director

of Bridge so obviously we can sort this out another way,”

Riep pleaded. The director was silent.

“Can we

get moving?” the detective asked.

“Sure, well it

was nice to meet you and I think we will see each other

again very soon,” Riep told the two Bridge executives, and

then turned off his recorder.

He was escorted to

an unmarked car, noting that the men bore a “striking

resemblance” to the private security guards the Ugandan

elite hire to protect their homes and businesses.

Inside the car was another man, who identified

himself as an attorney for the government of Uganda, but

whom Riep later told the press he learned was a lawyer

working for Bridge. They passed the Kampala Central Police

Station and kept driving for more than an hour and a half,

arriving at a two-room, clapboard police station in

Kyengera, home to a front office and a holding cell. Four

media outlets waited outside, filming Riep’s arrival. Two

Bridge officials held forth about the danger Riep

represented to the community. Riep, in his dissertation,

said that the station’s police were confused about why he

was there, which raised further questions about who the men

who had “arrested” Riep at the café were.

He was

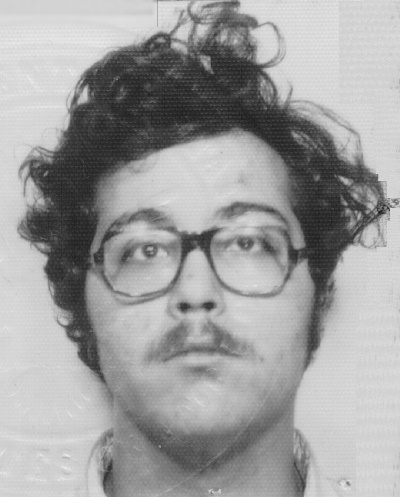

interrogated by the police for several hours and told that

Bridge had taken out an advertisement in a major local paper

a few days earlier, on May 24. The ad warned the public Riep

was “wanted by the police,” underneath a photograph of his

face.

He was

interrogated by the police for several hours and told that

Bridge had taken out an advertisement in a major local paper

a few days earlier, on May 24. The ad warned the public Riep

was “wanted by the police,” underneath a photograph of his

face.

Riep in his dissertation later described the ad as “a very

risky proposition in a country with an upswing of violent mob justice

happening in the streets of Kampala.”

They were trying to get him killed.

After being released on

bond, Riep was required to return the next day for more questioning.

Fortunately for him, he had consistently signed into logbooks at schools

under his own name and affiliation, according to

reporting by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation,

and Bridge could produce no staff witnesses or other evidence to

sufficiently back up the claim that he had impersonated Bridge personnel.

The police dropped the charges, he later wrote, but they warned him that

Bridge may “come after you again.”

………

The High Court in Uganda soon moved to

shutter 63 Bridge schools on the basis that they were “operating illegally

because they have no provisional or other licenses.” Bridge

fought the order

in court but lost, though it has continued fighting and has not closed its

schools.

The Uber model. Remember Uber does not do background checks either, and has had some horrifying incidents of assault.

………

Bridge had been battling a growing coalition of opponents for

years, establishing a reputation as a sharp-elbowed company that responded

aggressively to any hint of criticism.

In 2014, a Kenyan court

ordered

Bridge schools closed in one county for

not complying

with the minimum safety and accountability standards for educational

institutions. When the county education board moved to enforce the court’s

decision two years later, Bridge

responded by suing the board and its director on the grounds that they had not followed the

required process.

………

The investigation of the Bridge

investment has become the center of a controversy at the World Bank over

investor responsibility when it comes to “negative externalities” — the

euphemistic term for damage that results from investments — and the nature

of the accountability process inside the IFC, the World Bank’s financing

arm.

………

Seven

years after David Nanzai discovered the note on his desk, the case remains

unresolved and officially unsolved, and the victims uncompensated. The

teachers we spoke to for this story have all left Bridge schools. But the

IFC is working on a new framework to deal with such “negative

externalities.”

Translation, a few rapes is OK, because investors make money.

………

The

Intercept also asked the IFC, Chan Zuckerberg, and the Gates and Omidyar

funds what, if any, responsibility investors had to remedy the situation.

“Any instance of harm to a child is unacceptable,” said a Chan Zuckerberg

spokesperson. “We would refer you to the letter from Bridge Kenya on the

practices it has in place to safeguard students and immediately

investigate reports of any safety issues.”

A spokesperson for

Omidyar’s Imaginable Futures said the fund owns a 2.7 percent stake in the

company. “We refer you to the statement provided to you by Bridge Kenya,”

the spokesperson said.

………

The company commissioned an

education consultancy, Tunza, to evaluate its practices and policies. The report, published in

2020, found that public schools faced far greater rates of abuse than

Bridge schools, though the methodology betrays an extraordinary confidence

in Bridge’s reporting systems. For public schools, the study relies on

anonymous surveys of students. For Bridge schools, the report largely

relies on actual cases that were reported to higher-ups and investigated.

The report, funded by Bridge, gently suggests that Bridge ought to, at

some point, also survey its student body to find out if its assumption

about nearly universal reporting through official channels is accurate.

The consultants were hired to obfuscate, not find the truth. McKinsey & Company writ small.

………

Despite its efforts to address these

issues, there have been other troubling cases at Bridge Kenya, both before

and after the 2016 incident at Mukuru Kwa Reuben.

Court

records show that in 2017, several prepubescent female students were

sexually harassed by a teacher at another Bridge school in Mukuru. The

teacher was arrested, and the case is still being adjudicated in court.

Because the efforts are window dressing.

This is how foreign investment works in the third world.

It is abusive and exploitative because that is what the investors want, and so that is what the developed nations, and the constellation of civil society organizations deliver, because that is who signs their paychecks.

Unless and until some of the senior executives get tried, convicted, and imprisoned in those countries, this will continue, because everything else is just a cost of business.